Last week I was faced with a very difficult decision, to go see the new Lego Movie or attend a lecture given by Dr David Rundle entitled “The Uses of Books in Late Medieval Culture”? Fortunately for you, I chose the latter and was rewarded handsomely! Within the space of an hour this erudite lecturer ruminated upon the fact that within medieval culture a book was not solely reading material but an object that within a specific moment had its own agency.

This specific moment is the presentation of the book itself. The book had agency in the presentation event because it created a social opportunity for both its producer and its royal recipient. For the producer of the book the presentation was an opportunity for patronage, and in accepting the book the recipient would have to show their largesse.

During this lecture I was struck by the fact that the content of the books were not fully recognised. While the significance of the book was widely acknowledged in medieval culture, literate people formed the minority within a culture dominated by illiteracy. Therefore the potential to fully engage with writing and realise the significance of a book’s content was reserved for those elite few who could both read and write.

Gaston may have had a point after all! Writing was central to medieval culture yet illiteracy resulted in an engagement with writing that was predominantly characterised by ignorance.

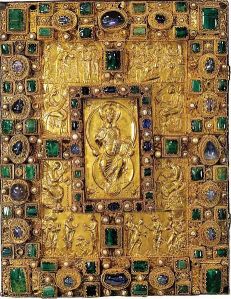

In his lecture Dr Rundle used certain manuscript illuminations depicting book presentation events as visual aids to further elaborate this fact. These illuminations usually involved an open book, with the presenter in a reverential kneeling position and the royal recipient ruminating upon the book’s content. The illuminations that I found particularly interesting were the ones that depicted a closed book being presented. In these representations it was clear that it was the book’s luxurious binding was the focus in their presentation.

Christine de Pisan presenting her expensively bound and decorated book to Isabeau of Bavaria (BL Harley 4431).

One of Dr Rundle’s visual aids was a manuscript illumination depicting Christine de Pisan presenting her expensively bound and decorated book to Queen Isabeau of Bavaria. Within this context it is clear that reading is not a book’s sole purpose. A book was also a means of demonstrating a person’s continuing social status which subsequently stimulated the development of more deluxe and luxurious forms of book binding, such as Treasure binding.

The “New Histories of the Book” module of the Texts and Contexts: Medieval to Renaissance MA in University College Cork introduced the notion that a book’s paratext, the extraneous elements of the book, are just as important as its content in understanding its context. Dr Rundle’s talk complemented this module by dwelling upon the book’s connection to social status within a medieval context. To conclude, when faced with a book as lavishly decorated and bound as the Codex Aureus of St Emmeram, how do you not judge the book by its cover?

For those who wish for superior discussions about palaeography or codicology, visit Dr David Rundle’s WordPress Blog!

Works Cited

Rundle, David. “The Uses of Books in Late Medieval Culture”. University College Cork, 2014.

Images Cited

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München. Codex Aureus of Sankt Emmeram. Photograph. 2009. Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 03 Mar. 2013.

British Library. Isabeau de Baviere. A photographic reproduction of a manuscript illumination. 2013. Christine de Pisan. Wikimedia Commons. Web. 03 Mar. 2014.

gemma4scott. Belle and Gaston. Cartoon. n. d.. fanpop! Wikimedia Commons. Web. 03 Mar. 2014.